Hi there,

We’ve got so used to computing getting ever cheaper that it has been an article of faith that it will keep getting cheaper. Rodolfo Rosini, CEO of a stealth startup and long-time EV member asks us to think differently. What if we are reaching the fundamental physical limits of classical models of computation, just as our economies depend on cheap computation for their effective functioning?

We are sending this out on Saturday so you can have a chance to relax over this challenging idea. Tomorrow’s newsletter is deep with analysis of AI, so keep a cup of coffee handy for that as well.

The comments are open for members and Rodolfo will be around to respond.

Best,

Azeem

P.S. Guest posts represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily mine.

Correction: This essay has had one correction since publication. See footnote 8 for clarification.

The Great Computing Stagnation

TLDR; The Great Stagnation

1 puts forward the contrarian argument that the United States (and, by extension, allied Western economies) have reached a plateau due to a lack of technological innovation. A strong argument can be made that computing has entered such an era and that can be validated by observing the cost of computation and its impact on productivity. Moreover, it is due to deteriorate even further in the next decade.

In many industries, Wright’s Law

2 —that each 20%-or-so improvement in manufacturing processes leads to a doubling of productivity—holds. In the technology sector, Wright’s Law manifests as part of Moore’s Law. First described in the 1960s by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, when he noticed that the number of transistors in integrated circuits appeared to double almost year-on-year. Since then this has become the foundation of a covenant between marketing and engineering forces, a drive to build products across the computing stack that exploit this excess computing capacity and reduction in size

3. The promise is ever faster and cheaper microprocessors, with an exponential improvement in computing capability over time.

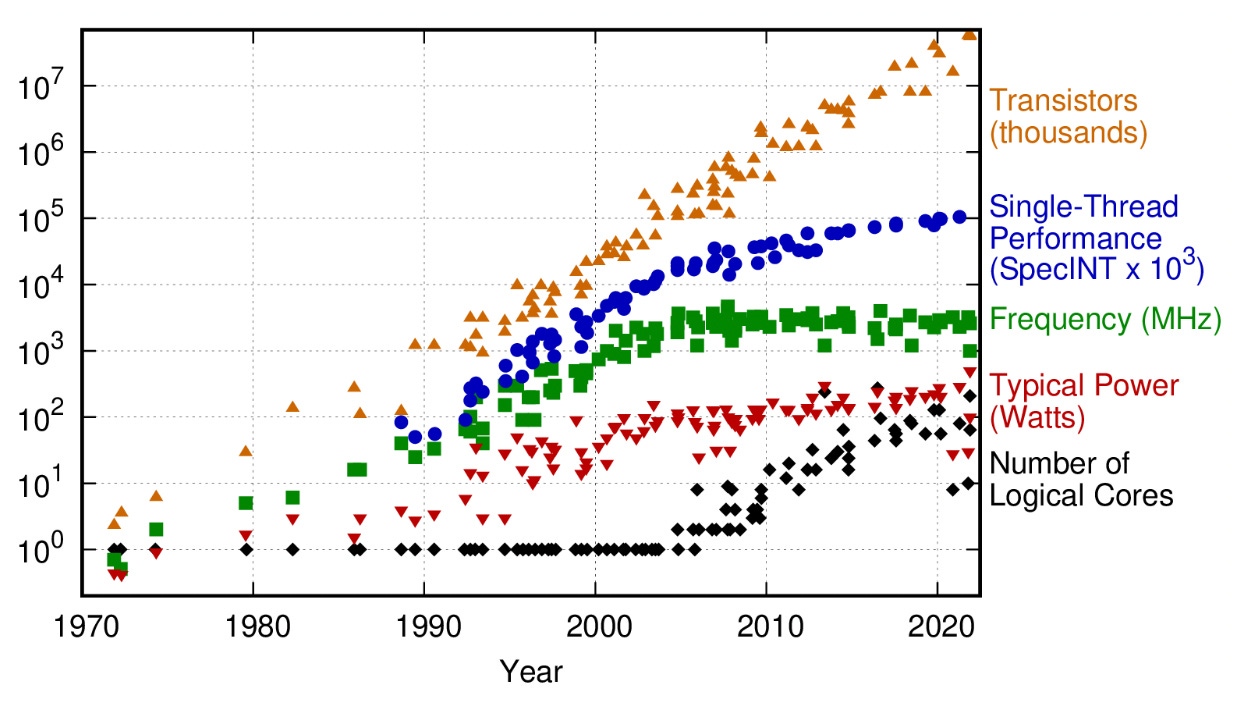

By necessity, the different forces that comprised Moore’s Law have changed. For decades, Dennard scaling was the force behind Moore’s Law with transistor size and power usage halving in synchrony, enabling the amount of computation per unit energy to double (the latter known as Koomey’s Law). In 2005 this scaling started to break down due to current leakage causing the chip to heat up, and with it the performance of chips with a single processing core stalled.

To try to maintain its computing growth trajectory, the chip industry transitioned to multi-core architectures: multiple microprocessors ‘taped’ together. While this may have prolonged Moore’s Law in terms of transistor density, it increased complexity across the computing stack. For certain types of computing tasks, like machine learning or computer graphics, this delivered performance gains. But for the many general computing tasks that didn’t parallelize well, multi-core did nothing

4. To put it bluntly, for many tasks computing power is no longer growing exponentially.

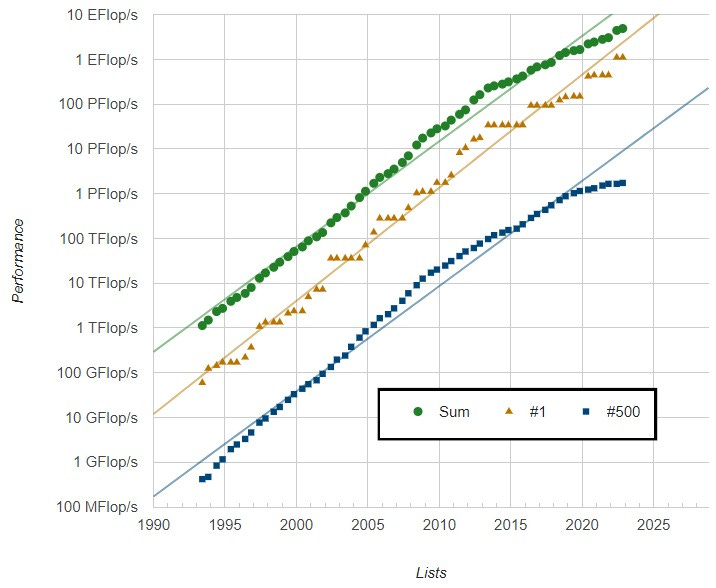

Even in multi-core supercomputer performance, there is a clear inflection point around 2010 when one looks at the aggregate computing power of the TOP500 (the ranking of the world’s fastest supercomputers).

What is the impact of this slowdown? The increasingly critical role computation has played across disparate industries suggests the impact is immediate, and will only get more significant if Moore’s Law falters further. Take two extreme examples: increased computing power and deflating costs account for 49% productivity growth for oil exploration in the energy industry, and 94% growth in protein folding prediction in the biotechnology industry. This means that the impact of computing speeds is not limited to the technology industry, but that the majority of economic growth of the past 50 years was a second-order effect driven by Moore’s Law, and that without it the world’s economy could stop growing.

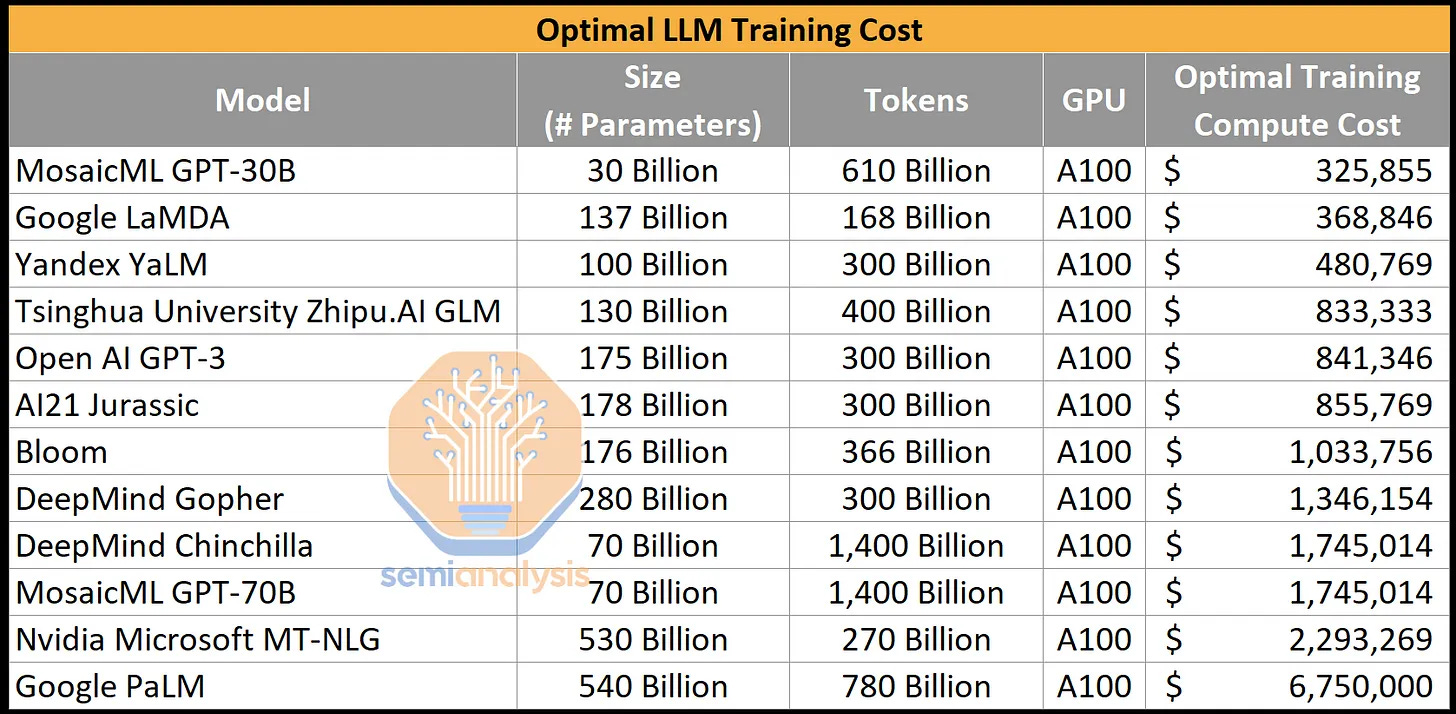

A more prominent example of the need for more computing power is of course given by the rise of artificial intelligence. Training large language models (LLMs) today can cost millions of dollars and takes weeks

5.

The future that machine learning promises simply cannot be delivered without a continued increase in number-crunching and data scaling. With the growing ubiquity of ML models in consumer technology, heralding a ravenous, and likely hyperbolic demand, for compute in other sectors, cheap processing is becoming the bedrock of productivity. The death of Moore’s Law could bring the consequences of the Great Computing Stagnation to bear. Today’s LLMs are still relatively small and easy to train compared to multimodal neural networks that might be needed to reach AGI. Future GPTs and their competitors will require exceptionally large and powerful high-performance computers to improve, even accounting for optimization.

At this point, one may be feeling sceptical. After all, the End of Moore’s Law has been foretold many a time before. Why should it be right now? Historically, many of these predictions have arisen from engineering challenges—roadblocks to better manufacturing. Time and again, human ingenuity has overcome these hurdles. The difference now is that the challenge isn’t one of engineering and intelligence but about the limits imposed by physics.

Too hot to handle

Computers work by manipulating information. And when they manipulate information, some of this information is thrown away as microprocessors merge computing branches or overwrite registries. This is not free. The laws of thermodynamics place strict boundaries on the efficiency of certain processes, and—perhaps surprisingly—this applies to computing just as much as it does to the steam engine. This cost is known as Landauer’s limit. It is the tiny amount of heat dissipated during each computational operation: about 10-21 joules per bit. (For comparison, Usain Bolt expends about 100 kJ, running 100m.)

Given how small this is, Landauer’s was long considered a curiosity that could be safely ignored. Yet, engineering capabilities have advanced to the point that this energy scale is in reach as the real-world limit is estimated at 10-100x larger than Landauer’s boundary due to other overheads such as current leakage. Chips have hundreds of billions of transistors operating at billions of cycles per second; the numbers add up. Moore’s Law has perhaps one order of magnitude growth left

6 before reaching the thermal barrier. At that point, existing transistor architectures will not improve energy efficiency further, and the amount of heat generated will prevent packing transistors any closer together.

If we don’t figure this out, then what the industry values will change. Microprocessors will be throttled, and industry will compete on the lesser prize of marginal energy efficiency. Chip size will balloon. Just look at the series 4000 NVIDIA GPU card: it is the size of a small dog and draws up to 650W of power, despite using a higher-density process. This prompted the NVIDIA CEO, Jensen Huang, to go on stage in late 2022 and declare that “Moore’s Law is dead”—a statement denied by other semiconductors companies despite being mostly correct.

The IEEE publishes a yearly roadmap of semiconductors and the latest assessment is that 2D scaling will finish by 2028, and that 3D scaling should fully kick in by 2031. 3D scaling—wherein chips are stacked on top of each other—is already pervasive, but in computer memory rather than microprocessors. This is because memory has far lower heat dissipation; nevertheless, heat dissipation is compounded in 3D architectures, so active memory cooling is becoming important. Memory with 256 layers is on the horizon, and the 1,000 layers mark is predicted to be achieved by 2030.

Returning to microprocessors, multigate device architectures (such as Fin field-effect transistor and Gates-all-round)

7 that are becoming the commercial standard will continue to carry Moore’s Law in the coming years. However, due to the inherent thermal issues, no true vertical scaling is possible beyond the 2030s. Indeed, current chipsets carefully manage which parts of the processor are active at any time to avoid overheating even on a single plane.

The crisis

A century ago, Robert Frost asked whether the world will end in frost or fire, and while it seems that the universe might end as a cold void, the end of computing is very much heralded by fire.

Perhaps an alternative would be to simply accept the increased power usage and just scale up manufacturing of microprocessors. We are already using a significant fraction of the planetary electricity supply for that very purpose. In Ireland, just 70 data centers consume 14% of the country’s electricity output. The rate of scaling of energy production makes it marginally more expensive to continue Moore’s Law scaling after this point. Other possible pathways will involve a series of one-off optimizations at the design (energy efficiency) and implementation level (replacing old designs that are still in use to the latest technologies), that would allow economies like India, China, and other developing economies to catch up and increase the overall global productivity.

After the end of Moore’s Law, humanity will run out of energy long before it reaches a limit on the manufacturing of microprocessor chips, and the pace of computing cost deflation will stagnate.

Quantum computing is being touted as a path beyond Moore’s Law, but its many unknowns, combined with the decades of development still needed for commercial viability, make this unhelpful for at least the next 20-30 years.

There is a severe capability gap approaching in the next 10 years, one that is not being addressed by technology incumbents, by most investors, or by government agencies. The collision of Moore’s Law and Landauer’s Limit has been known for decades and is arguably one of the most critical events in the 2030s. Despite its importance, vanishingly few are aware of it. Until now, no one has even deigned to give it—the Landauer Crisis—a name.

https://www.exponentialview.co/p/the-great-computing-stagnation